After nineteen sanctions packages, enforcement is the real test

Without stronger enforcement, the EU will remain stuck in a familiar cycle: announce, applaud, then watch as targets adapt

Russia’s war on Ukraine continues to test Europe’s unity and resolve. Nineteen sanctions packages later, the EU faces a hard truth: new measures alone won’t deliver. If previous rounds had been fully enforced, would we need nineteen packages (and already debating a twentieth)? The sheer number suggests a systemic weakness.

The previous packages have been undermined by uneven implementation and loopholes, which have allowed restricted goods and funds to slip through. Unless these gaps are closed, new packages risk becoming symbolic gestures rather than effective tools. Without stronger enforcement, the EU will remain stuck in a familiar cycle: announce, applaud, then watch as targets adapt.

Russia continues to import billions of euros’ worth of battlefield and high-tech components. Investigators have found thousands of foreign-made parts inside Russian missiles, drones, helicopters, and even in Iranian-designed drones deployed by Russia. These are the microelectronics, sensors, and precision tools at the heart of modern weapons systems. Around 90% of the foreign components found in Russian weapons come from countries that have sanctioned Russia, including the EU, the US, Japan, and others.

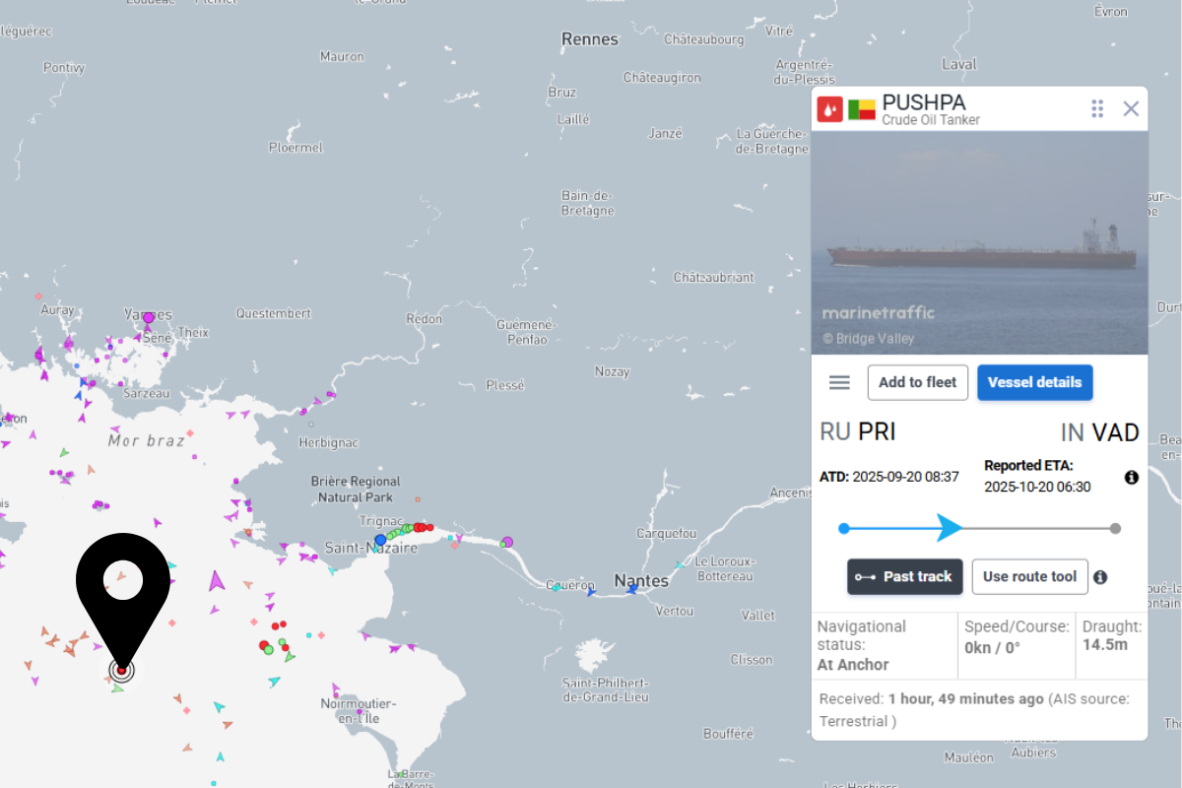

Russia’s domestic industry simply doesn’t produce these parts at the scale or sophistication needed so has built a sophisticated network to circumvent the trade barriers. Direct exports from the EU and US have dropped sharply, but indirect shipments have surged. China and Hong Kong have become major conduits for high-tech goods. Russian procurement agents use multi-hop routes: A chip might be sold to a distributor in East Asia, passed through Central Asia, and finally shipped into Russia, sometimes openly, sometimes under false documentation.

They also exploit legal grey zones, using shell companies and trading firms in China, Turkey, and the UAE to buy Western electronics and resell them to Russian clients. Russia has even legalised parallel imports, allowing branded goods to enter without the manufacturer’s permission.

Still, sanctions work. Russian importers often pay two to five times the original price for these components, facing unpredictable delivery times and frequent scams or seizures, which slow down Russia’s war production and make it harder to scale. A recent Chatham House study described Russia’s defence industry as suffering from “innovation stagnation”, forced to rely on Soviet-era designs and incremental upgrades despite record spending. The more we tighten enforcement, the harder it becomes for Russia to modernise. But they won’t stop without enforcement.

Moreover, while military aid takes time to reach Ukraine, cutting off Russia’s access to critical components immediately slows its ability to produce weapons. Every loophole closed is a missile not built, a drone not launched, a radar system not repaired. And the return for Europe’s own security is high: Enforcement is far cheaper than matching Russia’s production or intercepting every missile. It hampers their rearmament, forces them to rely on outdated systems, and reduces the threat of precision strikes on European infrastructure.

So what does better enforcement look like?

First, build EU-wide enforcement capacity: shared intelligence, regional enforcement clusters, and dedicated funding for national authorities. A chain is only as strong as its weakest link, so we need to reinforce the exposed outposts.

Second, close circumvention routes: mandatory “Russia clauses” in export contracts, end-user declarations and stronger checks, and better coordination between sanctions and financial intelligence units are essential. This will disrupt the multi-hop supply chains and legal grey zones that Russia exploits.

Third, cut off Russia’s access to high-tech inputs and post-sale support: tighter export controls, restrictions on software and cloud services, and compliance audits for high-risk goods are needed. No more after-sales support (repair parts or online support) for sanctioned items, and strict licensing for any technical assistance.

The EU’s 19th sanctions package includes important steps in this direction, such as anti-circumvention clauses and blacklisting third-country firms in China and Hong Kong suspected of rerouting tech to Russia. But these measures will only be as effective as their enforcement.

Adopting new packages with ever-longer lists of names keeps us reactive; only robust enforcement can break that cycle. If enforcement had been robust from the start, we could have disrupted supply chains earlier, closed loopholes faster, and reduced Russia’s ability to adapt.

As a twentieth package looms, the focus must shift from drafting lists to building enforcement mechanisms that deliver results on the ground and match the ambition of our policies: to weaken Russia’s war machine and bolster both Ukraine’s defence and Europe’s long-term security.

Rasmus Grand Berthelsen is Senior Director at Rasmussen Global and Lecturer at Copenhagen Business School.