Europe's race to build its Air Shield

Faced with threats edging ever closer, Europe is scrambling to build up its defences fast and almost from scratch

September came full of surprises: Nearly 20 Russian drones breached Polish airspace on 9 September, followed by more unidentified drone incursions in Denmark and Romania, and Russian fighter jets in Estonia. Poland and Estonia set NATO alarm bells ringing by invoking the alliance’s Article 4 in response.

As EU leaders gathered in Copenhagen at the start of October, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen stressed the urgent need for a European “drone wall” – a coordinated network of radars, jamming equipment, and counter-drone interceptors to neutralise threats before they reach sensitive airspace.

The proposed project, rebranded as the European Drone Defence Initiative, doesn’t just cover the EU’s eastern flank as initially envisioned, but the whole of EU airspace.

At the same time, a far bigger plan is gaining traction, one that could fold the so-called “drone wall” into a continent-wide defence network. The European Air Shield envisions a multi-layered air defence system, inspired by Israel’s Iron Dome, to intercept everything from drones to ballistic missiles.

But after decades of underinvestment and reliance on US protection, Europe faces a hard question: when – or if – such a shield could become a reality. And if governments do press ahead, what would that look like in practice?

The drone wall

The recent Russian drone incursions, seen as a ploy to test NATO’s air defences and political resolve, have exposed some uncomfortable truths.

Modern warfare isn’t about sheer numbers anymore; it’s about precision at scale. Swarms of coordinated strikes that blend cheap drones with high-end weapons can now deliver devastating blows to both civilians and critical infrastructure.

Ukraine offers stark examples. Over the summer, Russian drone and missile attacks reached the seat of the Ukrainian government and the EU delegation in Kyiv.

The asymmetry is brutal: mass precision is cheap for attackers, but costly for defenders. NATO’s response to the recent incursions was effective, but expensive. The military alliance used Patriot missiles worth €3 million to down drones that cost €20,000 or less to make. That scenario is unsustainable in the long run.

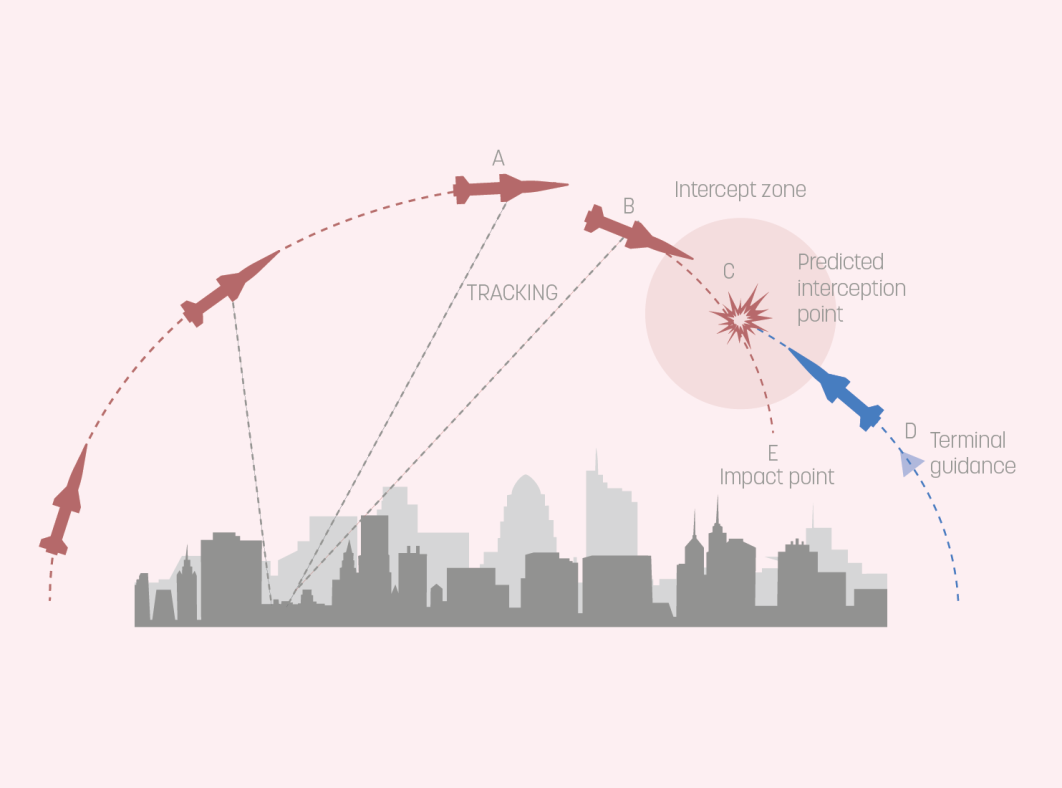

To combat swarms of cheap attacks, a layered air defence system might offer the best solution. Low-cost systems would first be deployed against smaller threats, saving fighter jets and high-end missiles for more devastating attacks such as ballistic and hypersonic strikes.

According to this logic, the “drone wall” would constitute the first defensive layer of the broader Air Shield. Its job would be to detect, track, and neutralise drones and loitering munitions. To shoot them down using kinetic interceptors and directed energy weapons (DEWs) – lasers that can cost as little as €1–10 per shot – would be a bargain option when compared to the price of Patriots.

To make the “drone wall” a reality, some in Brussels are looking east.

“There is a great deal we can learn from Ukraine, and at the same time we must provide them with protection and financial support, because in return they are helping us in the drone war,” said Estonian MEP Riho Terras. “It is an investment in our own defence.”

The European Air Shield

A European Air Shield won’t be easy or cheap to build. The EU will need to overcome political differences, stockpiling issues, and costs.

What’s more, the EU cannot simply replicate Israel’s Iron Dome. It protects a small territory with dense population centres against predominantly short-range threats. By contrast, Europe’s populations are scattered across a vast area and face the full spectrum of Russia’s arsenal, from short-range Iskander missiles to long-range hypersonic Avangards.

A single dome spanning the continent is a fantasy. The plan instead calls for a patchwork of defence “bubbles” – multiple systems covering different territories, interlinked to provide effective coverage of Europe’s airspace.

Air defence is all about timing — to detect, track, and intercept in seconds. That demands precision and real-time coordination across borders, with radars in one country feeding data to launchers in another.

While projects like the German-led European Sky Shield Initiative (ESSI) – for joint procurement and maintenance – are already underway, there are challenges beyond just hardware. These systems must plug seamlessly into a common architecture: NATO’s Integrated Air and Missile Defence (IAMD).

It’s a familiar, if uncomfortable, principle for member states. Even while retaining full autonomy in procurement decisions, they would need to select configurations that prioritise interoperability with allied systems. That is where European politics bite.

Overcoming vulnerabilities

According to Chris Kremidas-Courtney, a senior fellow at the European Policy Centre, Europe faces a procurement dilemma.

Europe’s dependence on foreign defence systems — mainly American and Israeli — cuts both ways. It can accelerate deployment but risks eroding Europe’s strategic autonomy. While homegrown options exist for most threat ranges, there’s still no real substitute for Israel’s Arrow-3, a hypersonic interceptor built to stop ballistic missiles.

Adding to these concerns, Europe’s defence industry remains fragmented.

“Berlin backs IRIS-T and Patriot through the European Sky Shield Initiative, while Paris and Rome champion SAMP/T, and Oslo and others rely on NASAMS,” Kremidas-Courtney said. “Each nation is reluctant to surrender its own ‘champion,’ making common procurement and integration far harder than it should be.”

The challenge, therefore, isn’t only technological – it is political. A credible, layered defence system demands not just billions in investment, but a level of coordination Europe has historically struggled to achieve. That leaves the Air Shield dream years away.

(mm, cp, cm)