Tokyo drift: Why the EU is going all-in on Japan

China’s export restrictions on rare earths have prompted a surge of diplomatic engagement between Brussels and Tokyo

Torrents of European tourists have flocked to Japan lately to take selfies in front of Mount Fuji, sample a real matcha latte, and gorge on intricately-assembled sushi. The European Commission has been flying out there too – but with a very different agenda.

With 11 official trips this year, EU commissioners have visited Asia’s second-largest economy far more than any other non-EU country, a fact that has largely flown under the radar. But why?

Based on conversations Euractiv has had with a number of officials, the answer is that Brussels is seeking to learn from Tokyo how to de-risk from China, and how to counter Beijing’s chokehold over the world’s supply of strategically crucial rare earths – which further tightened this October.

Outreach began in April, after Brussels and Tokyo were caught in the crossfire of a global trade war that US President Donald Trump ignited with his so-called reciprocal tariffs.

Two days later, China retaliated with swingeing export controls on rare earths. Beijing dominates the global supply of the metals, which are used to produce everything from smartphones and computers to radars and fighter planes.

While the EU had long talked of “de-risking” from China, the new restrictions sparked panic among policymakers in Brussels and forced many of Europe’s struggling industries to delay or even shutter production.

Brussels, however, quickly realised that a key ally – Japan – had previous experience navigating a similar Chinese blockade.

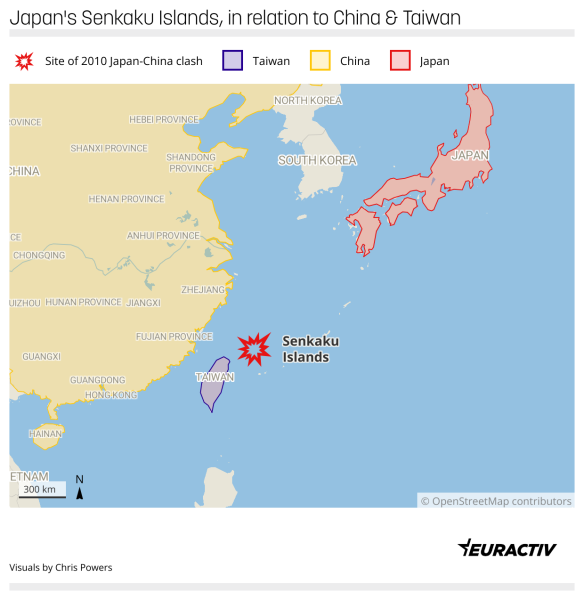

In 2010, a Chinese fishing vessel collided with the Japanese coastguard in its waters off the Senkaku Islands near Taiwan, which China calls the Diaoyu Islands. The incident triggered a diplomatic crisis that culminated in China banning the export of all rare-earth minerals to its East Asian neighbour.

The move, which alarmed Japanese industry leaders, caused Tokyo to rapidly diversify its political and economic ties across the Asia-Pacific region and bolster its relationship with Australia, another major source of rare earths.

Fifteen years later, experts argue that the EU can learn from Japan’s experience.

Elli-Katharina Pohlkamp, director of the Agora Strategy Institute, a geopolitical consulting firm, said the “wake-up call” that European countries experienced after the COVID-19 pandemic – when their supply chains’ heavy reliance on China was originally exposed – is one that “Japan already had in 2010.”

Pohlkamp said no country has institutionalised the notion of economic security to the same extent as Japan, which has embedded the concept in its national security strategy and passed legislation aimed at diversifying its trade links and strengthening supply chain resilience.

“This is why Japan is very interesting, because maybe they don’t have the full solution yet, but at least they have started putting one step after the other – because they felt the pain earlier,” Pohlkamp said.

Tokyo airlift

A month after China’s April export controls announcement, European commissioners began filing in and out of Japan, one after the other.

Leading the charge was Trade Commissioner Maroš Šefčovič, who met with Japan’s minister for economic security Minoru Kiuchi, Foreign Minister Takeshi Iwaya, and several business leaders, including the CEO of the Japan Organisation for Metals and Energy Security.

Days later, Economic Security Minister Kiuchi also met with Commission Vice-President for Tech Sovereignty and Security, Henna Virkkunen.

In July, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and the EU’s top diplomat Kaja Kallas were in Japan for the EU-Japan Summit, along with Council President António Costa. While there, Kallas met the foreign minister and the Japanese Defence Minister Gen Nakatani.

By October, the publicly available commissioner calendar showed 11 different commissioners travelling individually to Japan, each with their own agendas.

Only India had more commissioners visit this year, but that was due to a short visit by nearly the entire College in February. That was not followed up by a string of individual tours of the country.

From May to October 2025, the commissioners’ calendar recorded 85 engagements in Japan. Only the week of the UN General Assembly logged more commissioner-level meetings (175). The UN aside, Japan saw far more commissioner activity than any other country during the same period.

Asked about the reasons for the high number of visits, the EU executive all but admitted that the need to de-risk from China was the principal motivation.

“EU-Japan cooperation takes place within a rapidly evolving geopolitical and economic context,” a Commission spokesperson said. “In general, the EU seeks to diversify its trade relationships, strengthen supply chains, and reduce dependencies.”

The spokesperson added that economic security and trade diversification have also been “a key theme” among the G7 group of industrialised democracies in recent years, including under the Japanese presidency in 2023, when leaders published their first dedicated statement on economic security.

Two people familiar with the Commission’s thinking also confirmed that Beijing’s imposition of rare earth controls in April was a major reason for the renewed focus on Japan, which they said faces the same challenges as the EU in dealing with China.

Similarities in political culture – including a shared commitment to multilateralism, rules-based trade, and the need to combat climate change – have also strengthened the relationship between Brussels and Tokyo, the spokesperson said.

Analysts also noted that Europe’s approach to China is more like Japan’s than Washington’s.

“The United States has a very hawkish opinion and very much talked about decoupling from China,” said Pohlkamp. “The European Union and Japan, on the other hand, are more in favour of de-risking.”

A new and permanent state of emergency

Although no future visits by commissioners to Japan are currently planned, experts believe that China’s even more stringent restrictions on rare earths, announced earlier this month, only amplify the urgency of boosting cooperation between Brussels and Tokyo.

Under the new export regime – which mirrors Washington’s export controls on US-made semiconductors – products than contain even trace amounts of Chinese rare earths will require special licenses from Beijing before they can be exported. Use of the metals for military technologies, meanwhile, will “in principle” be banned.

Brussels ‘concerned’ by new Chinese rare earth restrictions

Defence

The European Commission said it was unsettled by China’s sweeping new export controls on strategically…

3 minutes

Alicia García Herrero, a senior fellow at the think tank Bruegel, said China’s move was carried out partly in response to Washington’s export restrictions on semiconductors but also in retaliation against US efforts to make Taiwan produce half of its chips in America.

The self-governing island, which Beijing claims as part of China, is the world’s leading manufacturer of advanced semiconductors. “I think they are really worried about the US pushing Taiwan in these negotiations,” García Herrero said.

The US-China rivalry, and Washington’s refusal to collaborate with like-minded partners, mean the EU and Japan will likely further strengthen ties over the coming years, analysts said.

However, some warned that the push by Brussels to reduce its strategic dependence on Beijing would be costly, and could spark a backlash from those worried about the environmental impact of rare-earth mining and refining, both of which are highly polluting.

“Ultimately, we might not manage, because you need a lot of resolve to do this,” García Herrero said. “China is also making us believe that there’s no way out – which they’re very good at.”

(cm, aw, jp)