Moody’s credit boss warns EU leaders to think carefully about defence spending

The Commission is pushing member states to take on new debt to boost defence spending, making credit ratings more relevant than ever

We don’t care whether you spend on defence or on farmers, but focus on growth.

That, in a nutshell, is what the chief credit officer at Moody’s, the world-famous credit agency that rates governments, told Euractiv in an interview, amid the Europe-wide push to finance a defence spending boom, perhaps using new debt.

Government defence spending serves primarily national security goals. However, Atsi Sheth, Moody’s chief credit officer, argues that policymakers must also consider how their investments affect the economy if they want to maintain good credit ratings. Moody’s focuses – among other things – on whether new investments in defence generate growth, create jobs, and spur productivity in other sectors.

“Can you execute in a way that increases a virtuous cycle of growth through investment?” Sheth asked.

The European Commission is actively incentivising EU countries to take on new debt to boost defence spending. In that context, credit ratings from agencies such as Moody’s matter. Financial institutions closely monitor those ratings when lending cash to governments. Put simply, the poorer the rating, the higher the interest rates. That means Moody’s opinions could impact a country’s bottom line.

NATO allies will finance the sharp increases in defence spending they promised with debt. If they all stick to spending 3.5% of their GDP on defence, that would likely add €500 billion in new debt, assuming that 80% of the money comes from borrowing, Sheth estimated.

That probably won’t be a problem for a country’s credit rating, she said, if they make sure that cash turns into jobs, grows other sectors, and generally has a positive impact on the economy.

When assigning ratings, Moody’s considers factors that positively affect inflation and growth. Sheth said that if a government’s defence debt benefits the economy, there’s no reason to expect a negative impact on its credit profile.

Experts, however, have characterised defence spending as an investment with poor returns. That’s because only governments are buying the gear, and they ultimately hope never to have to use the weapons they buy, meaning purchases can slump in times of peace.

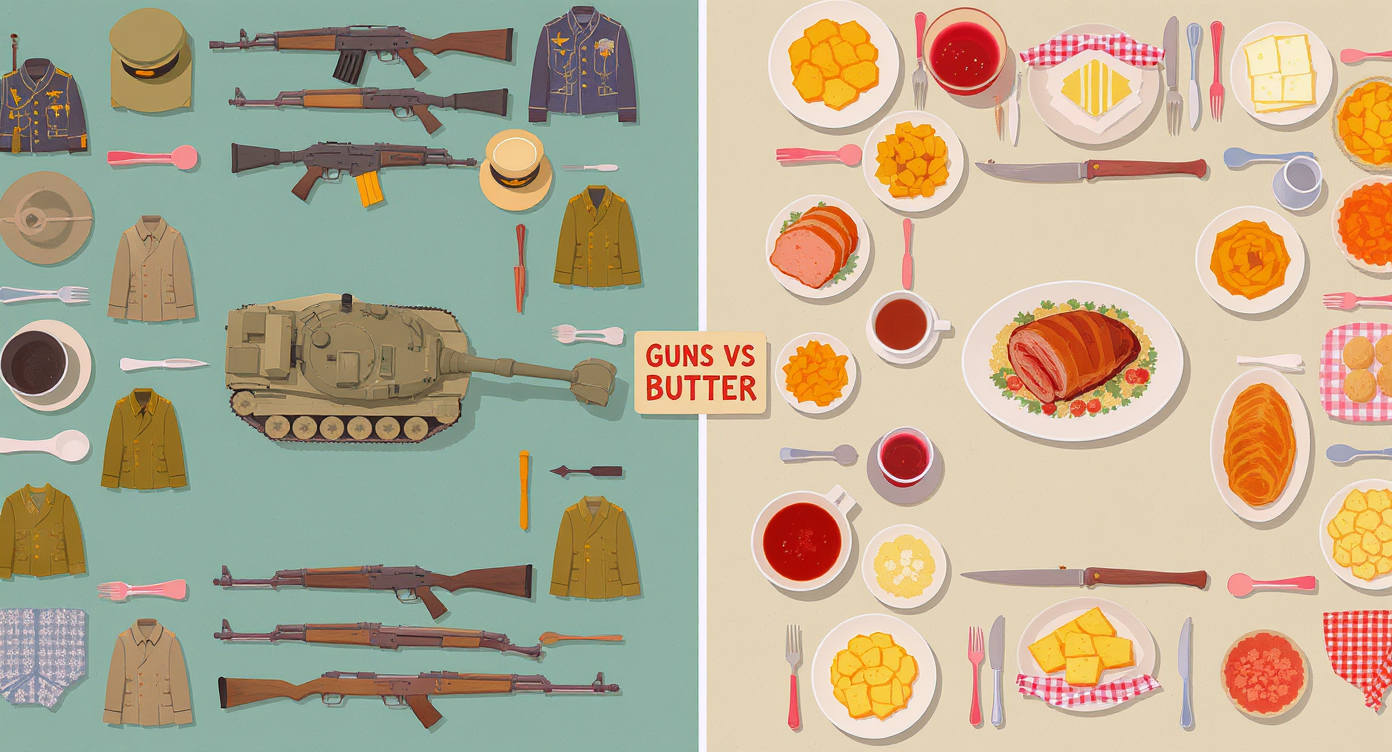

Kill the Guns vs Butter debate

Even if it’s too early to see how defence spending is impacting economic growth, the effect on the overall economy can be significant, Sheth said.

With billions flowing into defence firms’ coffers, governments can spur the economy and their ratings in myriad ways. For example, defence spending could spill over into other industries that are closely linked to it, such as the tech sector. That could have a multiplier effect on the economy, boosting jobs and tax revenue.

Sheth drew a parallel to the guns-versus-butter debate of the last century, in which governments sparred over whether to spend on defence or social programmes.

“You may decide that you’re going to spend it all on butter and not on guns, but if that spending on butter doesn’t lead to any longer-term infusion into the growth, you’re just spending,” Sheth said.

That rationale is starting to be adopted by some governments, too.

Romania’s defence minister, Liviu-Ionuț Moșteanu, said in October that his country’s military spending must create jobs, social benefits, and other positive impacts to justify the higher pricetag. France has also traditionally invested in its domestic defence industry to achieve similar benefits.

(cm)