Can Brussels save Slovakia's bears?

Brown bears are strictly protected under the EU Habitats Directive and can only be killed under exceptional circumstances

BRATISLAVA – The European Commission is mulling over whether the Slovakia’s bear cull – which has scrambled past 200 this year already – breaches EU nature protection law, with criticism mounting from green groups, including in neighbouring Poland.

In April, Bratislava approved the killing of up to 350 brown bears – roughly one-third of its estimated population of 1,000-1,300 – following a series of deadly bear attacks. The move sparked outrage among conservationists, who argue the cull violates the EU’s Habitats and Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) Directive, which protects vulnerable species.

The controversy flared up again last week, when Greenpeace Poland filed a formal complaint with the Commission, warning that Slovakia’s actions threaten Poland’s small population of around 130 protected bears, which frequently cross the shared border. The group also accused Bratislava of failing to conduct a required environmental impact assessment that would account for the entire cross-border bear population.

Brussels weighs its options

Brown bears are strictly protected under the EU Habitats Directive, and their killing is only permitted under exceptional circumstances – such as for public safety or damage prevention – and must be proven to be the last resort.

Greenpeace and oppostion Slovak parties, such as the liberal opposition Progressive Slovakia (PS) oppose the measure. Liberal MEP Michal Wiezik maintains that the cull is illegal under EU law.

According to Wiezik, Brussels recently warned Slovakia’s environment ministry that its limits on public participation in granting culling exemptions breach the Aarhus Convention – which guarantees access to environmental justice – and that double authorisations for both state and private hunters contradict the Habitats Directive.

“If these breaches are confirmed, the Commission can initiate infringement proceedings that could lead to a case before the European Court of Justice,” Wiezik told Euractiv.

A Commission spokesperson confirmed to Euractiv Slovakia that the EU executive has been reviewing the Slovak government’s cull decree for several months, noting that Bratislava is “responsible for ensuring compliance with the Habitats Directive in any emergency intervention.”

Slovakia submitted its mandatory Habitats Directive report in July 2025, which is now being assessed by the European Environment Agency before the Commission’s final review in the coming months.

The Slovak government has not reacted to Greenpeace’s complaint at the time of publication.

To hunt or to be hunted?

The Slovak government justified the mass cull after a 59-year-old man was killed by a bear in March – the third fatality in two years. It introduced looser hunting rules and declared a state of emergency across most of the country.

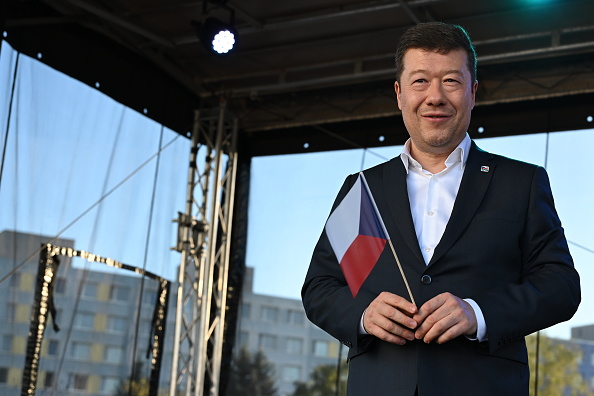

“It’s elementary logic: the more bears there are, the more encounters and damage,” Environment Minister Tomáš Taraba said back in March, adding that Slovakia’s bear population “is growing” and requires broad population control. He compared Slovakia’s actions to Japan’s own bear management policies, claiming that when Slovakia follows suit, “it sparks hysteria.”

By early November, around 211 bears had been killed in Slovakia, according to Greenpeace Slovakia, including through hunting, “intervention” shootings and accidents. Last year, 144 bears were killed – 92 shot – yet the number of attacks has continued to rise, Greenpeace Slovakia told Euractiv.

“The government approved the culling of 350 bears to allegedly prevent attacks, but paradoxically, this year we have the highest number of bear attacks on record,” said Greenpeace Slovakia spokesperson Miroslava Ábelová. Nineteen attacks have been reported so far this year, injuring 17 people – compared to 16 injuries in 2024.

Ábelová also accused the government of “completely failing” to educate the public on how to avoid bear encounters and instead “spreading panic.”

The ministry, she said, is not tackling bait sites – where hunters leave food to lure bears for easier shooting – nor addressing unsecured waste or nearby cornfields that attract animals toward human settlements. “These baiting practices teach bears to associate humans with food, making conflicts inevitable,” she added.

Ursia, a Slovakian non-profit association, noted that in many locations where bear attacks occurred, including fatal ones, hunting bait sites were found.

From forest to fork

Adding to the controversy, Slovakia allows meat from culled bears to be sold for human consumption if it meets hygiene standards – a practice that lies outside EU jurisdiction.

The meat, infamous for hosting tiny roundworms that infest digestive tracts, must be cooked at a temperature of at least 75°C to reliably make it safe for human consumption.

Wiezik, who submitted a formal inquiry to the Commission in June, said the European executive confirmed that potential infringement proceedings would not affect the legality of commercialising bear meat, as long as Slovak law permits it.

For now, Brussels is watching closely – but Slovakia’s hunters are still pulling the trigger.

(cs, aw)